This Is What Movies Look Like When They’re Alive

Three films built with nerve, craft, and zero safety nets

Most of us have more movies available than we could watch in ten lifetimes, and every now and then it is worth trying something different.

Take these 3 films. Three very different genres. All built with real intention, craft, and nerve. These are not background movies. They are the kind that pull you in, take their time, and stick with you long after the credits roll.

Alrighty then….. Let us get into it.

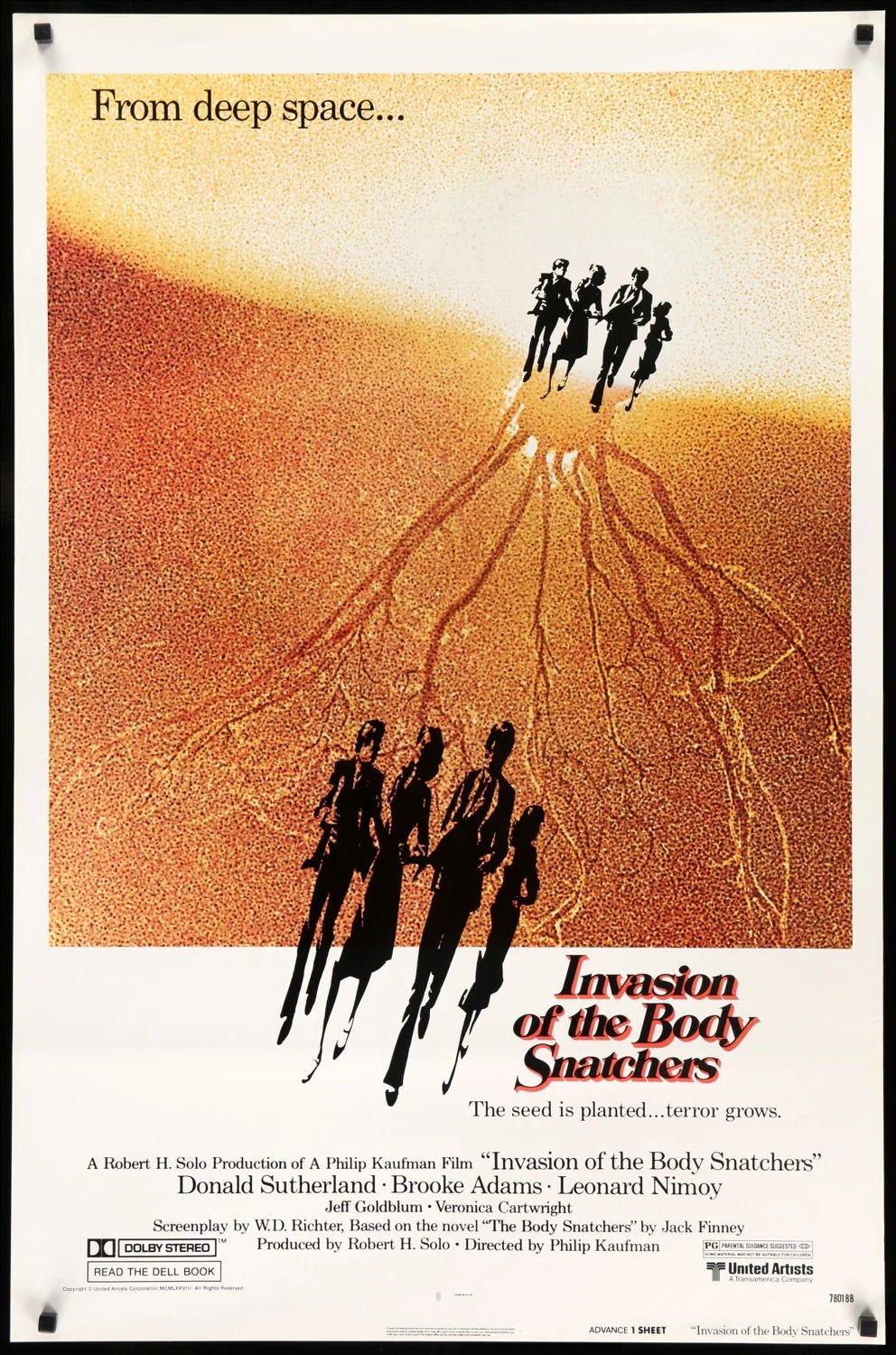

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

(1978)

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by W D Richter

Cinematography by Michael Chapman

Produced by United Artists

This might be the best remake ever made. Period.

That statement lands harder when you place the film in its moment. Invasion of the Body Snatchers came out in the late 70s, at the tail end of Vietnam, Watergate, and a decade where trust in institutions, neighbors, and authority had completely eroded. This is a movie born out of cultural exhaustion and quiet suspicion. It understands that paranoia does not come from monsters. It comes from watching the familiar slowly turn foreign.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers is paranoia cinema done right. Pitch perfect in tone, execution, and restraint. It never screams. It whispers. And that is why it works. Philip Kaufman ( The Right Stuff, Quills) understands that the scariest thing is not monsters. It is the feeling that something is wrong and you cannot quite prove it.

The story follows a group of ordinary people in San Francisco who slowly begin to realize that the people around them are being replaced. Not killed. Replaced. Perfect physical copies grown in pods that look the same but feel empty inside. No emotion. No empathy. Just function. As the invasion spreads quietly through homes, workplaces, and friendships, the characters are forced to confront a nightmare where survival depends on staying awake, staying human, and trusting almost no one. The horror is not the invasion itself. It is how easily it blends into everyday life.

Kaufman lets doubt spread the way it does in real life. Nothing explodes. Nobody believes you at first. The threat creeps in through conversations, glances, pauses. The horror is social before it is physical.

Donald Sutherland and Brooke Adams anchor the film with grounded, deeply human performances. There is a scene that still blows my mind every time: On a city street, Brooke Adams tries to explain to Sutherland that her husband has changed. Not in any obvious way. He just is not the same person anymore. The same goes for her neighbors and friends. Something is missing. There is no feeling behind their eyes. She cannot explain how or point to a single concrete detail. She just knows something is wrong, and it is terrifying her. As she talks, the film cuts to everyday street footage of people around them. People riding buses. Walking to work. Going about their lives. Faces blank. No emotion. Nothing overtly wrong. Much of this was not staged. It is real street footage, people reacting to a camera pointed at them, caught off guard, slightly empty, unintentionally perfect. Placed in the paranoid context of the scene, it becomes chilling.

This is where the film becomes genuinely unsettling. Those people are not doing anything wrong. They are just empty. In the context of what she is saying, those images become horrifying. These people do look wrong. That is filmmaking. That is tension without tricks.

Michael Chapman’s cinematography keeps everything grounded. Natural light. Real locations. Nothing flashy. It feels like a documentary that slowly turns into a nightmare. The city becomes hostile without changing at all. That is incredibly hard to pull off. San Francisco is not stylized or romanticized. It simply exists, and that normalcy is what allows the fear to grow.

This film has influenced everything from political thrillers to modern horror. You can feel its DNA in stories about conformity, loss of identity, and mass denial. It is a masterclass in suspense and paranoia. It trusts silence. It trusts implication. It trusts the audience to connect the dots. And that ending still hits like a punch to the throat.

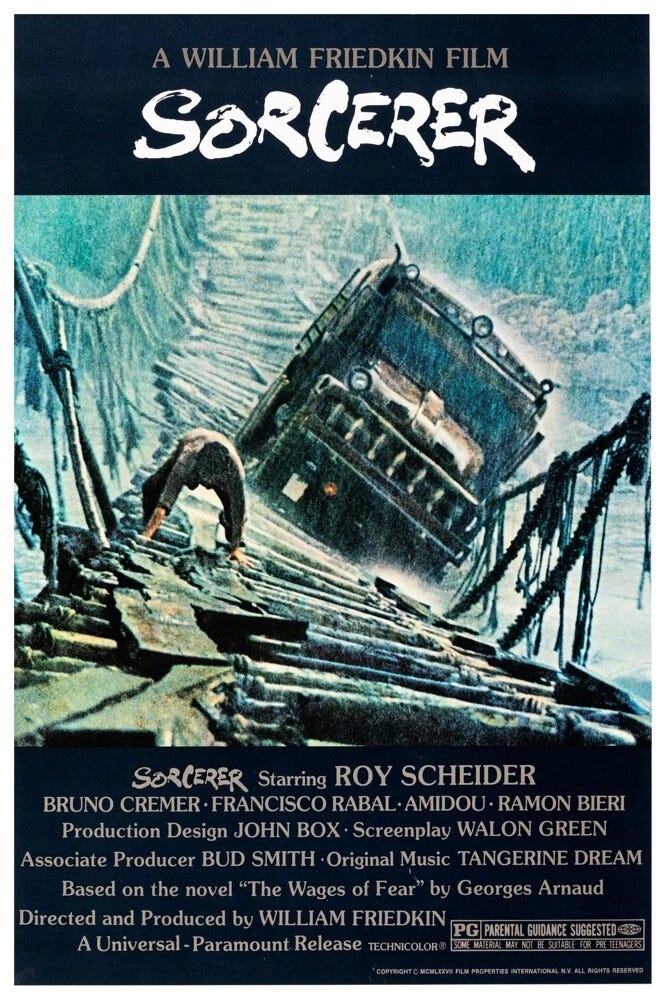

Sorcerer

(1977)

Directed by William Friedkin

Written by Walon Green

Cinematography by Dick Bush and John M Stephens

Produced by Paramount Pictures

William Friedkin’s Sorcerer arrived at exactly the wrong moment and paid the price for it. Released the same year as Star Wars, audiences walked in expecting another supernatural rollercoaster from the director of The Exorcist and instead got something far more brutal and adult. This was not escapism. This was cinema staring straight into the abyss. The film bombed, critics were confused, and for years it was written off as a failure. Time has been very kind to it, because time favors films that do not beg to be liked. Today, Sorcerer is rightly considered a full blown classic and, for me, a top five film from that insane decade that was the 1970s.

The film follows four men from different corners of the world, each on the run from violent pasts and moral dead ends. They end up trapped in a remote South American town with no way out, until they are offered a job that is essentially a death sentence. Transporting unstable explosives across hundreds of miles of jungle, rotten roads, and collapsing bridges. If they succeed, they earn their freedom. If they fail, they die. From that point on, the film becomes a slow march toward fate, where survival depends on discipline, luck, and how long a man can keep fear from taking control.

Sorcerer is an eternal story. Desperate men. No future. No clean past. A job so dangerous it feels less like employment and more like a delayed execution. Friedkin does not rush any of this. The opening act alone is fearless. Long, patient, and merciless in how it introduces these characters. Four men, four corners of the world, four moral sinkholes. Terrorists, criminals, murderers, fugitives. Friedkin makes you sit with them, understand them, and feel the weight of the choices that landed them there. By the time they end up in that jungle, you already know they are dead men walking. The only question is how long they will last.

Friedkin tells the story with a documentary like discipline that was already disappearing by the late seventies. There is no romanticizing of danger. No heroic framing. No safety net. Everything feels heavy, slow, and punishing. The heat is real. The mud is real. The machines are real. You can feel the environment grinding these men down minute by minute.

Once the journey begins, the film becomes a masterclass in tension without manipulation. There is no score telling you when to be afraid. No editorial shortcuts to manufacture excitement. Just engines rattling, tires slipping, rotting bridges, rain, wind, and men barely holding themselves together. Friedkin’s cinema verité approach makes everything feel physical. This is not abstract danger. This is mechanical danger. One wrong vibration, one bad angle, one lapse in focus, and everything explodes.

And then there is the bridge sequence. One of the greatest sequences ever put on film. No dialogue. No exposition. No tricks. Just two trucks, a rope bridge, a violent storm, and pure dread. Friedkin turns geography into an antagonist. Every shot has weight. Every cut matters. The camera placement is exact. The pacing is merciless. This is not spectacle for applause. This is fear earned through precision and restraint. It is filmmaking stripped to its bones.

Culturally, Sorcerer represents the last gasp of a certain kind of American cinema. A moment when studios still trusted filmmakers to challenge audiences instead of soothing them. When directors were allowed to make films that were bleak, uncompromising, and uninterested in likability. Sorcerer does not offer hope. It does not offer redemption. It does not hold your hand. It tells you the truth and walks away.

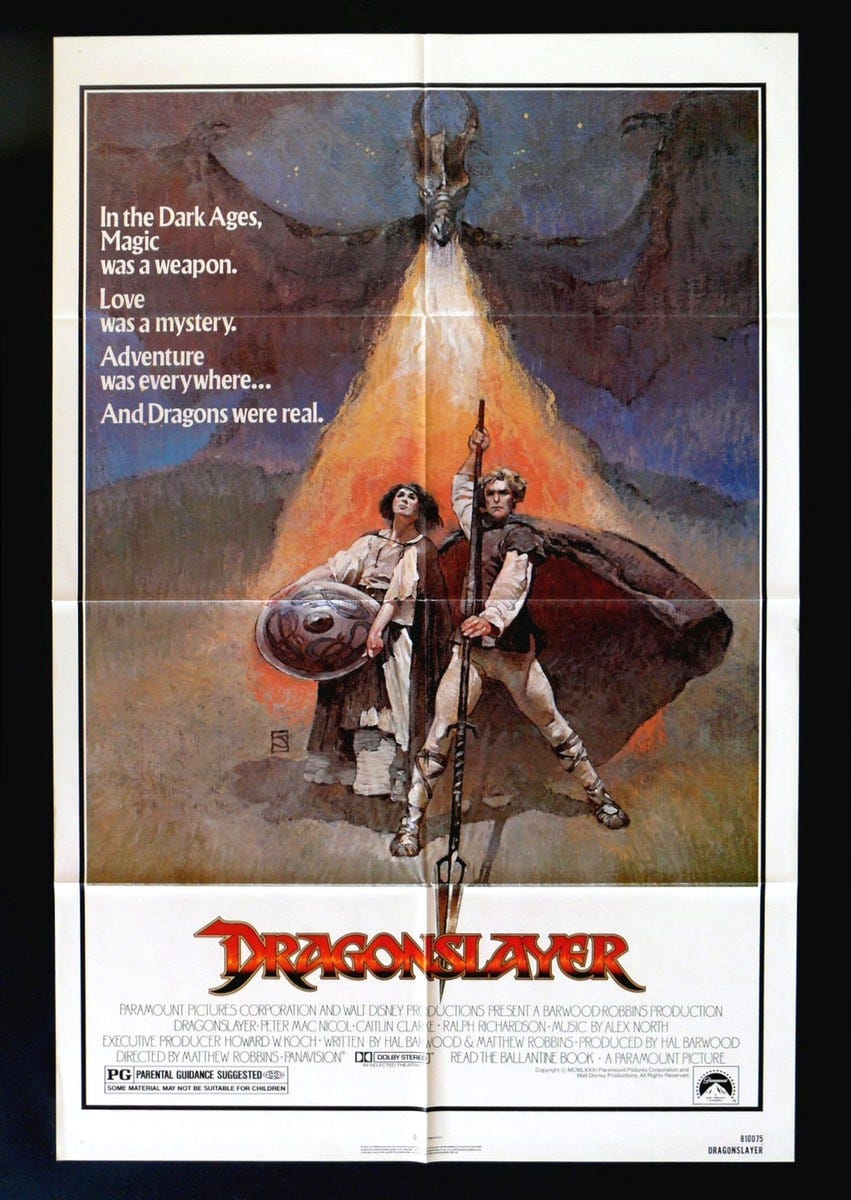

Dragonslayer

(1981)

Directed by Matthew Robbins

Written by Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins

Cinematography by Derek Vanlint

Produced by Walt Disney Productions and Paramount Pictures

In the late seventies and early eighties, something strange happened at Disney. For a brief moment, they grew some real balls. The studio started funding serious, adult leaning projects that had nothing to do with talking animals or comfort viewing. Most of them flopped, and the experiment did not last long, but the films that came out of that window were bold and fascinating. The Black Hole. The brilliant Never Cry Wolf. Tron………and Dragonslayer.

This is the film that made me want to become a cinematographer.

What hit me then, and still does now, was how next level the filmmaking was. The textures. The lighting. The production design. The way the image felt carved instead of lit. Derek Vanlint’s cinematography was operating on a completely different wavelength than most fantasy films before or since. Darkness was not avoided or filled in. It was embraced. Fire became the primary light source. Faces disappeared into shadow. Stone looked cold. Mud looked wet. Armor looked heavy and miserable. This world felt lived in, dangerous, and old.

Before you even get to the dragon, the film announces itself through restraint. Nothing feels decorative. Nothing feels clean. These sets are worn. These people are tired. Survival is the only currency that matters. This is not fantasy as spectacle. This is fantasy as physical experience.

The plot follows Galen, an inexperienced apprentice forced to step into a role he is not ready for after the death of his mentor. A kingdom lives in fear of a dragon that demands regular sacrifice. The people are desperate. The rulers are pragmatic to the point of cruelty. There are no easy choices, only bad ones and worse ones. The film never flinches from that reality.

What makes Dragonslayer special is its balance between scale and intimacy. Yes, there is a dragon, and it remains one of the most convincing creatures ever put on screen. Not because of flash, but because of behavior. The dragon feels like an animal. Territorial. Intelligent. Cruel when necessary. But the film never forgets the human cost around it. Quiet moments matter as much as the epic ones.

Seeing this film projected in 70mm as a kid permanently rewired my brain. The depth, the contrast, the texture. Light and darkness were part of the storytelling, not decoration. The recent 4K restoration only confirms what was always there. It makes a staggering amount of modern fantasy look flat and sterile by comparison. Say what you will, but most films today look like porn next to this.

Culturally, Dragonslayer exists before fantasy was sanitized. Before everything needed to be softened, explained, or turned into a franchise. It trusted its audience. It trusted patience. It trusted atmosphere. It understood that fear and wonder come from restraint, not noise.

***Quick side note before you dive in. If you can, always watch these in their original aspect ratio. Many of these films were shot in “2.35 to 1 aspect ratio” (well at least of ONE of the ones we are talking here today is,) a wide cinematic frame designed to use every inch of the screen. For future reference…know that streamers often crop the sides of a great film to fit your 16x9 TV or Ipad (fuck me), chopping off the sides and quietly destroying composition, blocking, and visual storytelling. It is not a small difference. It is massive. Demand the full frame whenever possible or look for it if you are really into the film (actually the answer is easy… BUY a physical version of it!. You will literally be seeing more of the movie and you get to keep it.)

Ok, thank you for making it this far!. Adios!

bring back beautiful movies!!!! loved this read