2 PERFECT THINGS

From divine genius to diesel-fueled hell. The unbearable beauty of Amadeus and Das Boot.

Some movies aren’t just great, they’re freakishly, annoyingly perfect. The kind that make you want to quit whatever you’re doing and just stare at the screen in awe. This series is about those films. The ones that nailed it so completely that every shot, sound, and performance feels inevitable. They don’t just hold up, they redefine what “holding up” means. Today’s pair? One divine opera of envy and genius, and one claustrophobic descent into hell. Amadeus and Das Boot.

Two perfect things.

AMADEUS (1984)

Directed by Miloš Forman | Cinematography by Miroslav Ondříček | Written by Peter Shaffer.

I remember seeing Amadeus in a theater with a girlfriend, thinking I was buying tickets to a stuffy period piece where I might sneak in a make-out session. I was fifteen, stupid, and full of hormones. What I didn’t know was that this movie would crawl into my head and never leave.

From the first frame, when F. Murray Abraham’s Salieri begins his confession, I was hooked. Both of us sat there, hypnotized by a man consumed by envy and brilliance. Abraham gives one of the greatest performances in film history, carrying the story on the back of his jealousy, self-loathing, and warped admiration for Mozart. Tom Hulce is perfect opposite him, a mad prodigy wrapped in laughter and chaos. Elizabeth Berridge as Constanze broke my teenage heart. Every scene in this film vibrates with passion, pain, and joy. I’ve seen both the theatrical and director’s cut, but for me, the original release is flawless. It doesn’t need one extra frame.

What makes Amadeus so perfect isn’t just its craft, it’s that rare alignment of theme, tone, and performance. Forman directs it like an opera, where every gesture, camera move, and laugh hits the rhythm of Mozart’s music.

Ondříček’s cinematography drenches 18th-century Vienna in candlelight and dust, making beauty look mortal. Salieri’s gaze becomes our own: we’re awestruck, resentful, desperate to understand how one man could channel divine perfection while another sweats for mediocrity. The film isn’t about Mozart’s genius; it’s about the agony of witnessing it.

Forman’s production design feels lived-in, not staged. Costumes by Theodor Pištěk look like they’ve actually been worn for years. The music isn’t background, it’s character, and what an incredible score this is, you could watch the film with your eyes close and it will send you to a beautiful place..

Neville Marriner and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields recorded nearly three hours of Mozart, much of it re-orchestrated to match the visual rhythm of each scene. The editing in the Requiem composition sequence still feels supernatural: image, sound, and emotion fusing into a cinematic crescendo that makes you forget you’re watching actors.

Behind the scenes, Forman shot the entire film in Prague, then still under Soviet control, to capture authentic Baroque architecture at a fraction of the cost. Most of the extras were local opera fans who treated the filming as a real performance. F. Murray Abraham stayed in character for months, often avoiding Hulce between takes to preserve Salieri’s hostility. Hulce, meanwhile, improvised parts of Mozart’s manic laughter, Forman loved it so much he rewrote scenes to use it as punctuation for genius. I can still hear his laughter in my head…infectious.

The film’s perfection lies in its contradictions. It’s decadent but raw, classical yet anarchic. It celebrates creation but obsesses over failure. When Salieri kneels before the crucifix and declares himself the patron saint of mediocrity, it’s both confession and triumph. Amadeus is the rare movie that makes envy feel human and genius feel unbearable. That’s real art.

This film IS perfect.

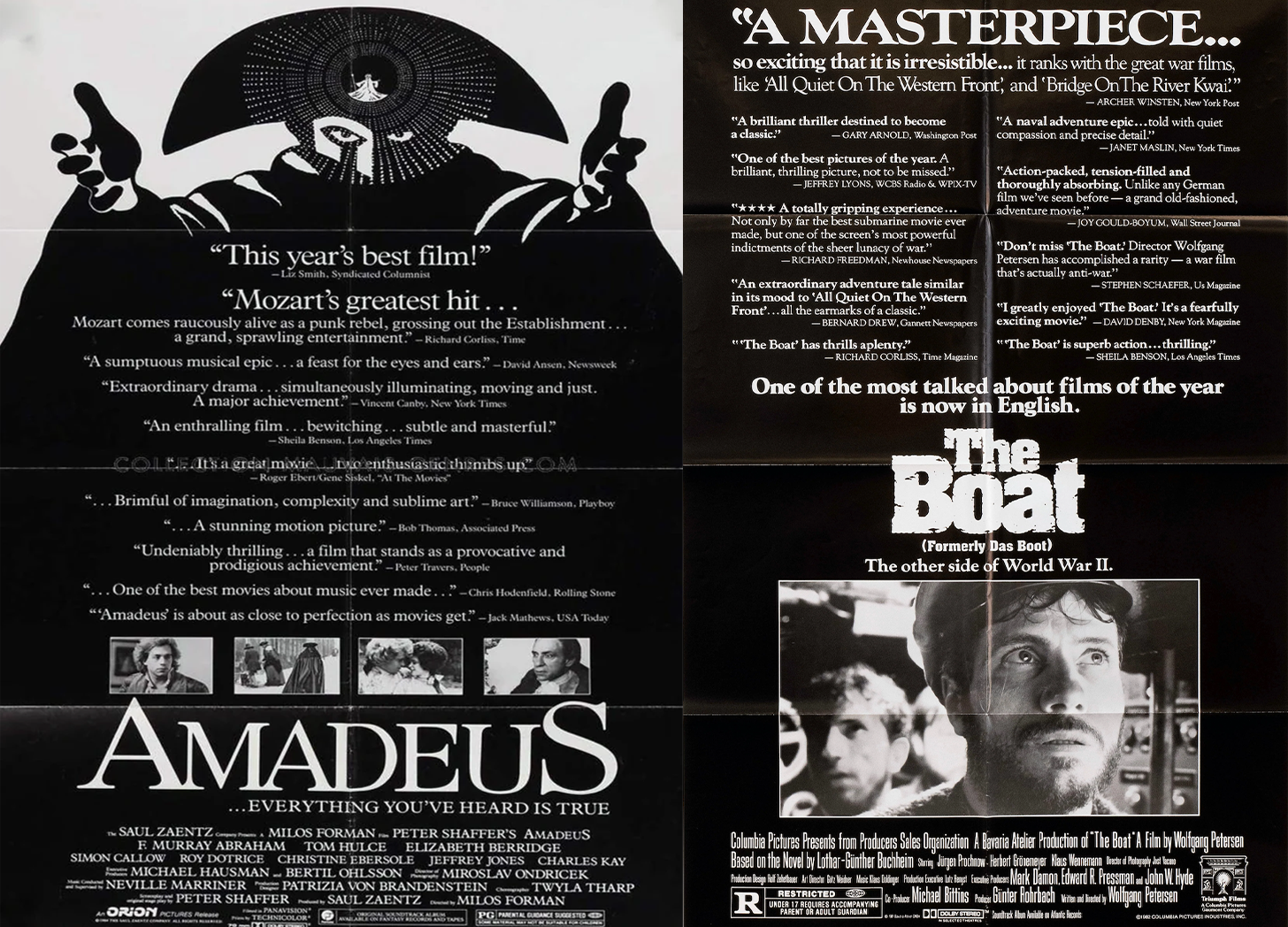

DAS BOOT (1981)

Directed by Wolfgang Petersen | Cinematography by Jost Vacano | Written by Wolfgang Petersen.

Calling this the best war film ever made might sound like a bar fight waiting to happen, but I’ll stand by it. Das Boot hit me during a time when theaters were full of great films every weekend. My older, pretentious cousin dragged me to a small art theater to see it, and I walked out shaken.

It was the first time I saw war through the eyes of German soldiers, human, frightened, far from the black-and-white villains of most war movies. This was the theatrical cut, edited down from the massive TV miniseries, and it was still overwhelming. Every frame dripped with sweat, oil, and despair. I had never seen a film that so perfectly captured claustrophobia, brotherhood, and the mechanical cruelty of survival.

The brilliance of Das Boot is that it’s a thriller disguised as a war film. Petersen traps us inside that submarine until we start gasping for air. The set was built as a full-scale replica of a Type VII U-boat and mounted on hydraulic rigs so it could tilt and shake with every depth-charge hit. The actors had to crawl through the narrow passageways while the camera crew, led by Jost Vacano, operated a specially built handheld rig to snake through the submarine’s guts. Every bead of sweat you see is real, the heat inside reached unbearable levels during filming.

What separates Das Boot from the rest of its genre is its moral clarity. Petersen never glorifies war. He gives us exhausted men trapped in a machine designed for killing, slowly realizing that heroism is a lie. The young war correspondent (Herbert Grönemeyer) becomes our eyes, documenting not victory but decay. The captain (Jürgen Prochnow) carries authority like a burden, his face carved by responsibility and quiet dread. The ending, when the crew finally escapes the sea only to be annihilated by Allied bombers, is devastating. It’s not tragedy for drama’s sake….it’s the purest cinematic statement on the futility of war.

Production stories only deepen the respect. Petersen pushed for obsessive realism. The sound team recorded in actual submarines to capture the metallic groans of pressure. The actors were told to avoid sunlight for weeks to keep their skin pale and sickly. Prochnow reportedly stayed up nights studying footage of real U-boat captains to mimic their stoicism under stress. Petersen himself suffered claustrophobia during filming but refused to open the set to relieve tension, he wanted the cast to feel trapped. It worked.

Das Boot is pure experiential filmmaking. You don’t watch it; you live inside it. The film’s rhythm mirrors the sonar pulse, tense silence, sudden chaos, breathless calm. Its technical perfection serves a spiritual purpose: showing that even the so-called enemy bleeds, jokes, dreams, and dies the same way. It’s the anti-Top Gun.

What makes it perfect isn’t the size of its spectacle but the precision of its empathy. Few films make you feel the weight of existence like this one. Every clang of metal and flicker of red light reminds you that survival is not victory. Das Boot remains the standard…a monument to craft, humanity, and cinematic courage.

This film IS perfect.

Find the best version you can, dim the lights, kill the notifications, and let them do what movies are supposed to do…wreck you a little, then rebuild you better.

And if you’ve seen them before, watch them again. See how fresh, how sharp, and how alive they still feel. Some films age. These two just keep getting louder.